Couldn't we just talk about the weather instead?

Politics, religion and all things divisive.

28 August, 2008

27 August, 2008

20 August, 2008

Race

Whenever I want to be intellecually offended and annoyed but challenged, I read David Stove. One of his most offensive papers is "Racial and Other Antagonisms", wherein he argues that "racism" is a word for what everyone knows it true. Yet the more time I spend with nice people, the more I think Stove might have been on to something.

Prima facie he was saying that we should all believe in racism and anyone who didn't was simply in denial. He went even further to ridicule the term, claiming that something so obvious requires no "-ism"; no more than the believe that the sun rises in the east should be labelled "eastism".

When I first read that essay, I struggled to see precisely what his mistake was. Then I realised that what he was actually arguing against was not what I thought racism was. The paper set out to argue that there are racial differences that are recognisable and are born out statistically. I think he argues this point relatively successfully so I had trouble seeing how his argument could be right and his conclusion wrong. Then I saw that he had done nothing to prove any particular racist theses in the superiority of some races over others. Likewise he blythely dismisses the objection that many of the characteristics he discussed might be social rather than genetic. It was then I decided that he was wrong for those two reasons, that for racism to be true it would have to be the case that certain races were genetically inferior. The "racism" that Stove showed to be commonsense was simply the belief that racial differences exist. But if racism means either racial prejudice or belief in the inferiority of other races, there's no defence for that.

Now, within the circles in which I move, all discussion of race is taboo. (In the narrow sense, of genetic difference, lineage etc. Discussion of ethnic differences is encouraged when it's sympathetic to the underdog.) This has led to the strange phenomenon that people who do discuss genetic differences in terms of race are looked at askance.

So much so that even generalisations about clearly cultural phenomena are frowned upon and criticism of other cultural practices are off limits. I flout this occasionally for trivial topics; I understand that it's just a generalisation but for me, if the question is not morally-laden, it's worth going out on a limb and guessing. For example, I told a Chinese friend that she'd definitely like liquorice despite having just waxed lyrical on how the world is divided into liquorice-lovers and liquorice-haters. I confidently told her that all Chinese people like liquorice (so far I've been right) because star anise is a staple of Chinese cuisine.

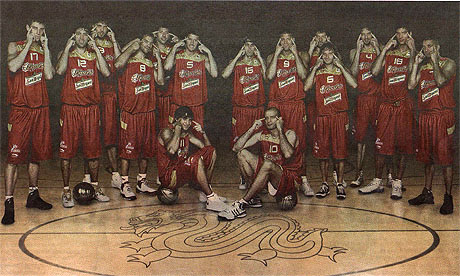

Recently I discovered that this attitude only exists in the Anglosphere, Europeans are not nearly as sensitive. For example, when French people (my sample set is 2) hear about the Spanish basketball team's slant-eye gesture, they don't see it as inherently offensive, they interpret it as affectionate. Likewise, even asian people who've grown up in asia (my sample set is 1) don't find it offensive, simply because they're tough enough to take a joke.

Recently I discovered that this attitude only exists in the Anglosphere, Europeans are not nearly as sensitive. For example, when French people (my sample set is 2) hear about the Spanish basketball team's slant-eye gesture, they don't see it as inherently offensive, they interpret it as affectionate. Likewise, even asian people who've grown up in asia (my sample set is 1) don't find it offensive, simply because they're tough enough to take a joke.That's not meant to be a criticism of asians living in western countries, they've a right to be sensitive after the childhood teasing. But still, it's interesting to see this difference.

I'd also like to add that people who want to combat racism shouldn't use the arguement that genetic diversity doesn't match up exactly to our everyday notions of race. This may or may not be a good characterisation (depending on whether or not you thing all genes should be equally weighted). The problem is that it allows that we could justify hatred of other races if it turned out that we were more different genetically. The reason we shouldn't has little to do with descent. We should treat all races equally because the evidence is that they are all equal in the ways that count, that is, in terms of intellectual potential, social characteristics etc. If we were to encounter an extra-terrestrial race that had these same similarities, we should treat them well regardless of whether or not their DNA is like ours (or if they even have DNA). If the overall result is that we can have a civil relationship with those aliens, we should.

18 August, 2008

God and Naturalism

I've just left a rather long comment on Lara's latest blog post. Thought I might put a copy here too.

Re Lennox's original piece

A professor of mine who was a student of Gould's has taught me to be wary of how people quote him. He made overtures to the religious community that have been taken out of all proportion (and now that he's dead he can't reply). But even a proper understanding of his "non-overlapping magisteria" thesis is completely incompatible with ID. Intelligent Design is the claim that we can infer things about the supernatural realm (broadly construed) by studying the natural world. In this article Lennox seems to understand Gould's claim that ne'er the twain shall meet. Why then is he quoting Gould in an article aimed at undermining Darwin? Because his real target is Dawkins! Why do people feel compelled to downplay Darwin's genius ever time Dawkins is rude and condescending to them? Beats me!

I think he's wrong about Sagan, though, when he says 'The Genesis statement is a statement of belief, not a statement of science. This is precisely the case with Sagan's assertion as well. He is expressing a personal belief that emanates from a world view, rather than science.' Seems to me Sagan was just marking out territory. To say "The cosmos is all there is, or was, or ever shall be." is more of an axiom than anything else; I think he's saying that no matter how far it extends in space or time, cosmologists should try to study it. Yes, tacit in this claim is the assertion that scientists should study any gods we might discover. But what's wrong with that?

Re Vic Stenger and your reply, which got printed:

You're right that it's underdetermined but, bearing in mind that you granted him "beyond reasonable doubt", that doesn't mean that we can't rule out certain things. So if we're using science to test the God hypothesis and it seems prima facie that there are no Judaeo-Christian God, then we bring in the Duhem-Quine thesis to insist that some auxiliary hypothesis failed the test.

"There's a skeptic in the room" is the best way but I think Stenger is right to say that 'a beneficent God would not deliberately hide from people who are honestly open to belief but do not believe for lack of evidence. The very presence of such non-believers in the world proves that a beneficent God does not exist.' If you grant him this, the hypothesis that was falsified is that God is not a tease. Or you can decide not to grant him that premise and simply say that people like Peter and myself are insincere in claiming to be open to belief.

Likewise, vestigial organs and childhood illnesses seem to indicate that organisms not designed by a benevolent god. Again, Duhem-Quine will allow you to lay the blame somewhere else, but where? A non-omnipotent god who couldn't have done any better? Some vague "best of all possible worlds"? (Remind me, where do you stand on the voluntarist question?)

You're quite right to use the Duhem-Quine thesis but please specify which auxiliary hypothesis have been falsified.

Re Paul Gittings's letter, your reply and on naturalism in general:

Well, the reason Gittings is attacking Lennox is not because of what appeared in the article but because of what he read between the lines. Lennox wasn't attacking Darwin in order to argue for Lamarckian evolution and from what you're said he understood Lennox's goal rightly enough.

Lennox didn't promote a god-of-the-gaps but. by invoking Gould, that's the logical result. (Because Gould's two magesteria cannot overlap, the more the natural realm grows, the more the supernatural must shrink, until all that's left is ethics and aesthetics, if that.)

As for naturalism being faith-based, that really depend on how you read it. Most claims of naturalism can be interpreted undogmatically (like Sagan's above) to mean just that science should never stop investigating, even investigate what has in the past been deemed supernatural. Methodologically speaking, it's one of the two extremes away from Gould's unhappy compromise (religious dogma being the other extreme). Still, I have to admit that it it a metaphysical claim of sorts. But of the broadest sort and somehow that seems a whole lot less metaphysical. It's the opposite to Wittgenstein's "The world is a collection of facts, not of things."